from the National Humanities Center |

|

| |

| NHC Home |

| Religion in Post-World War II America | ||

| Joanne Beckman Duke University ©National Humanities Center |

| |

Stained glass windows

Trinity Episcopal Church

Atchison, Kansas, 1974

Courtesy National Archives

(412-DA-14628)Contrary to what many observers predicted in the 1960s and early 1970s, religion has remained as vibrant and vital a part of American society as in generations past. New issues and interests have emerged, but religion's role in many Americans' lives remains undiminished. Perhaps the one characteristic that distinguishes late-twentieth-century religious life from the rest of America's history, however, is diversity. To trace this development, we must look back to the 1960s. As with many aspects of American society, the 1960s proved a turning point for religious life as well.

Up until the 1960s, the "Protestant establishment" (the seven mainline denominations of Baptists, Congregationalists, Disciples, Episcopalians, Lutherans, Methodists, and Presbyterians) dominated the religious scene, with the occasional Catholic or Jewish voice heard dimly in the background. References to American religion usually meant Protestant Christianity. Traditional Christianity faced some challenges in the first half of the century, especially from the literary elite of the 1920s, but after the second great war, the populace seemed eager to replenish its spiritual wells. At midcentury, Americans streamed back to church in unprecedented numbers. The baby boom (those born between 1946 and 1965) had begun, and parents of the first baby boomers moved into the suburbs and filled the pews, establishing church and family as the twin pillars of security and respectability. Religious membership, church funding, institutional building, and traditional faith and practice all increased in the 1950s. At midcentury, things looked very good for Christian America.

Over the next decade and a half, however, this peaceful landscape was besieged from many sides. The Civil Rights movement, the "Sexual Revolution," Vietnam, Women's Liberation, and new "alternative" religions (e.g., yoga, transcendental meditation, Buddhism, Hinduism) all challenged the traditional church and its teachings, its leaders and their actions. In the late 1960s and early 1970s, then, religion itself was not rejected so much as was institutionalized Christianity. The Church, along with government, big business, and the military—those composing "the Establishment"—was denounced by the young adults of the '60s for its materialism, power ploys, self-interest, and smug complacency.

The 1960s "revolution" has perhaps been exaggerated over the years. Studies show, for example, that while a large vocal minority of mostly middle- and upper-middle-class college students challenged traditional institutions and mores, many of their peers remained as committed to old-time moral and religious values as ever.

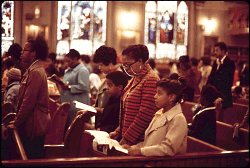

Traditional worshippers attend Holy Angel Catholic Church in Chicago, 1973 . . .

Courtesy National Archives

(412-DA-13786)

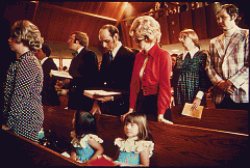

. . . and at St. Paul's Evangelical Lutheran Church in New Ulm, Minnesota, 1974.

Courtesy National Archives

(412-DA-15957)Nevertheless, the 1960s did swing wide a door that had never been opened before. A new vista of lifestyle options was introduced into mainstream America. In the religious sphere, this meant that mainline Protestantism or even the tripartite division of Protestant-Catholic-Jew no longer represented all of society's spiritual interests. Americans now had to take into account different kinds of spiritualities and practices, new kinds of leaders and devotees.

In the post-1960s era, the religious scene has become only more diverse and complex. The list is endless, but let us consider three examples that illustrate the pluralistic nature of American religion at the close of the twentieth century:

- the "boomer" generation of spiritual seekers

- the growth of non-European, ethnic-religious communities

- religious rights in the public square.

A Generation of Seekers

Even as diversity has increasingly fragmented American religious life in the last thirty years, religious interest remains as lively as ever. Vitality is seen both in the resurgence of more traditional, conservative expressions of Christianity and in the sustained interest in non-Christian alternatives. Two groups that have received much attention in recent years are the Religious Right, on the one hand, and New Age seekers on the other. Here we simply note that alongside a thriving conservative Christian community stands a very different expression of religious vitality. Its main participants are composed of what sociologist Wade Clark Roof calls the new "generation of seekers." These seekers are baby boomers who came of age in the 1960s and 1970s and are now in their thirties, forties, and fifties. Composing a third of the total population, this generation, because of its vitality and sheer size, is shaping contemporary culture in a profoundly new fashion.

One chief characteristic is that of being spiritual seekers. Some boomers have returned to the churches they grew up in, seeking traditional values as they now raise their own children. A larger number, however, never returned to the tradition of their childhood (predominantly Protestant, Catholic, or Jewish). Sociologists have estimated that 25 percent of the boomer generation have returned to church, but a full 42 percent have "dropped out" for good. These dropouts do not belong to any religious organization and claim no denominational ties. They eschew institutional formality and define themselves as seekers rather than traditionally devout or "religious." They might be open to "trying church" but are just as willing to sample Eastern religions, New Age spiritualism, or quasi-religious self-help groups of the Recovery Movement. For seekers, spirituality is a means of individual expression, self-discovery, inner healing, and personal growth. Religion is valued according to one's subjective experience. Thus seekers feel free to incorporate elements of different traditions according to their own liking. They shop around, compare, and select religious "truths" and experiences with what one historian calls their "à la carte" spirituality.

Books on angels, fascination with reincarnation and the afterlife, New Age music, the selling of crystals, popular Eastern garb, and best-selling recovery titles testify to how widespread and "mainstream" seeker spirituality has become in our society. Seeker self-discovery is far removed from conservative Christianity's traditional piety, but both point to the array of religious options now readily available and thoroughly respectable in late-twentieth-century America.

Ethnic-Religious Communities

Along with the new "seeker" spirituality, another sign of the dismantling of a monolithic "Protestant America" is the increasing celebration of religious particularity through the championing of ethnic identity, the politics of multiculturalism, and the growing communities of "new immigrants" from Latin America and Asia (those who moved to the United States since immigration restrictions were lifted in the landmark Immigration Act of 1965).

In the 1960s, the Civil Rights Movement provided a context for celebrating non-Anglo ethnicity for the first time. By the mid-1970s an ethnic revival celebrating the roots of African Americans, Mexican Americans, Native Americans, American Jews, and Asian Americans spawned. Suddenly non-Anglo, non-Protestant Americans were valorizing their own ethnicity, religions, and histories. In the 1980s, a politicized version of ethnic celebration emerged in the ideals of "multiculturalism," a philosophy of multiethnicity that sees America composed of a wonderfully diverse group of communities ineradicable in their ethnic character. Replacing the already old notion of America as the melting pot nation, or a citizenry bound together by a set of universalistic values (e.g., democracy, equality, justice), multiculturalism argues for the beauty of diversity, the essentialist nature of ethnic identity, and thus the necessity for cultural pluralism. We should encourage ethnic communities to celebrate their own histories, cultural distinctives, and religious traditions (Afrocentrism and bilingual education, for instance, are two key policies of the multicultural agenda).

With the number of immigrants from Latin America and Asia only growing in the 1990s, the issue of religious diversity or cultural pluralism looms larger than ever. Spanish speakers, for example, will soon outnumber English speakers in the state of California. Southeast Asians are making their home on both coasts and in the heartland as well (Laotians and the Hmong have established thriving communities in wintry Wisconsin and Minnesota).

A wholly new religious space is being carved out in the American landscape—a space that has little to do with the traditional ethnic divide between black and white or the religious division of Protestant, Catholic, and Jew. This religious site is different, too, from the New Age seekers and spiritual shoppers of the boomer generation. Americans are going to be exposed to multiple ethnic and "Two-Thirds" world religions as never before. While certain portions of the intellectual elite have been fascinated with the world's "great religions" (Hinduism, Buddhism, Islam) since the mid-nineteenth century, these traditions have never penetrated Main Street America. By the end of this century, however, Americans will increasingly encounter Buddhist neighbors, Muslim colleagues, and Hindu businessmen. These "foreign" religions will no longer be simply descriptions in school textbooks or exotic movie subjects. Indeed, advocates of cultural pluralism hope that the new religions will become as much a part of the American Way as historically Protestant orthodoxy.

Not only will new ethnic religions dot the landscape, but multiethnic religious traditions will emerge as well. Indeed a broad survey conducted by the Institute for the Study of American Religion reports that some 375 ethnic or multiethnic religious groups have already formed in the United States in the last three decades. Sociologists of religion believe the numbers will only increase in the coming years. Roman Catholic Mexican, Anglo, and Vietnamese Americans, for example, are beginning to celebrate a common Mass together in some parts of the country. Muslims of different sects are sharing mosque space in major cities. African Americans wearing kufi hats are singing Southern Baptist hymns in Chicago churches (with portraits of Martin Luther King, Jr., and Nelson Mandela gracing the walls). In sum, these young, thriving, and growing immigrant communities are introducing a whole new kind of religious pluralism into late-twentieth-century America. The real impact of immigrant communities remains to be seen, but religion in America promises to be more complex and diverse in the coming years than ever.

Religion in the Public Square

Another area in which the diversity of contemporary American religion manifests itself is in the escalating battles fought in the courts over religious practice in the public square. Most legal battles over religion center around interpretations of the First Amendment's religion clause: "Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof." The issues commonly raised, thus, concern questions about the "separation of church and state" (especially as violated by traditionally privileged Protestantism) and the free exercise of religion (especially as sought by minority traditions). Litigation and disputes over the First Amendment have increased dramatically since the 1970s and continue unabated today.

Historically, the courts have been loathe to rule on disputes within religious groups, questions concerning what constitutes "religion," and the legitimacy of personal religious practices. Concerning the free exercise of religion, however, the courts have intervened when traditional welfare questions or "common good" policies are involved. Under "traditional welfare," for example, Jehovah's Witnesses have been ordered to grant blood transfusions for their children, Christian Science parents have been convicted for refusing medical care for their children, and the marriages of child brides have been prohibited despite being customary practice among certain Hindu sects. The courts, then, will rule against certain religious practices when they believe a child's welfare is in serious jeopardy. "Common good" policies have led the Supreme Court to rule against the sacramental use of peyote by Oregon Indians. Protecting antidrug laws is considered absolutely necessary (i.e., banning certain drugs no matter what their usage) for the larger "common good" of the nation.

Aside from welfare and common good policies, however, the post-1960s courts tend to support the broad exercise of religious freedom. Since the 1970s, religious groups that have been traditionally marginalized have especially received a careful hearing. Landmark cases supporting practices within the Amish community (their children do not have to attend high school), the Hare Krishnas (the right to proselytize), and the Santeria religion (animal killings for ritual sacrifice are allowed) testify to the trend towards a liberal reading of the free exercise clause. In 1993 Congress passed the Religious Freedom Restoration Act to require "strict scrutiny" of any state or federal law that conflicts with the free exercise of religion. The Supreme Court struck down this act in 1997 (in a case involving city zoning laws and a church's renovation plans), asserting that Congress had overstepped its authority and that the act violated the separation of powers in the federal government. Since then several states have passed or introduced bills for state religious freedom restoration laws.

The second set of battles in the courts centers around the religious establishment clause. Since the 1960s "no establishment of religion" has been interpreted by many as requiring a strict "separation of church and state." The separation of church and state argument has been levied against traditional Christianity in particular. The focus of the battles has been in the public schools, especially, where the courts have sought to dismantle any practices of conventional religion. Both Bible reading and prayer that are directed by the school have been banned from public schools since the early 1960s. Despite ongoing efforts to appeal these laws (and most recently to replace prayer time with a "moment of silence"), the courts have not changed their stance. Legislation to include creationism alongside teachings on evolution in the schools has been continually struck down. In 1992, clergy prayers were abolished at high school graduations (although student prayers are allowed).

Some Christians have argued that such rulings do not protect against the establishment of a state religion but actually promote the religion of secular humanism. The Courts maintain, however, that a neutral zone can be created in the schools and do not see secular humanism as a religious belief. Just as the cultural trend towards supporting religious pluralism has led to a broad free exercise of religion for marginalized groups, so the courts have also taken a generally strict stance over the no establishment clause to ensure traditional Christianity does not take a privileged role once again in the public square.

Guiding Student Discussion

The overall goal of this lesson is to expose students to the increasingly diverse and pluralistic nature of religious life in late-twentieth-century America. Here are some topics to consider for discussion.

- Religion remains a very important aspect in American life today, but it has taken on new shapes and different forms. Two popular expressions of religious vitality in post–World War II America are conservative Christianity (again, see essay on the Christian Right elsewhere on this Web site) and spiritual "seekers." What kinds of factors (historical, personal, familial) draw some towards traditional religious practice and others to different and alternative ones? Is religion a matter primarily of belief (believing certain things about a transcendent being), practice (doing certain activities, following certain rules), or experience (feeling certain emotions, having a spiritual encounter)? What would a conservative Christian say? What would a spiritual seeker say?

- With the ongoing expansion of non-European, non-Protestant immigrant communities across the United States, students will increasingly encounter (if they haven't already) those of a different skin color, homeland, history, language, and religion. What different religious traditions have the students encountered so far? How do they think about religious differences? Why do we often scoff at or feel (if we're honest) frightened and isolated by those who believe differently from ourselves? What is the best way to learn about different religious traditions? How does one respect another's religion while believing one's own tradition is the correct one?

Students will begin to see how entwined religion is with other essential "identity" traits. Religion often goes hand in hand with one's ethnicity, nationality, and family history. For many, religion is not a matter of choice but one assigned by birth. Being Jewish, for example, involves both ethnic and religious identity. Can a Jew choose to become "not Jewish"? If one does not follow the tenets of Judaism, does one remain a Jew?

How can the United States be one, unified nation when so many different ethnic and religious communities live here? What does it mean to be American? Does America need one religion, one language, one political tradition? Who decides what values, beliefs, and practices are truly "American"?

- The most common, contemporary interpretation of the First Amendment's prohibition of the establishment of any state religion is that of a "separation of church and state." But this was not the primary concern of those who adopted the initial amendment. The First Congress of the United States (led by James Madison) was not concerned with the separation of church and state so much as the domination of one particular tradition over all others. They did not want a state-established church. Is it possible to separate one's religion from one's public life? If so, how does the government enforce the separation? If religion is an essential part of one's identity (like ethnicity, nationality), then how does one not bring religion into the public arena? The courts have implicitly acknowledged the difficulty of absolute separation of church and state for they have often opted, instead, to grant equal rights and protection to a multiplicity of religions rather than try and separate all religious elements from public life. What are the dangers of separating one's religion from public life? What are the dangers of not separating church and state?

Historians Debate

Those teaching and writing religious history are increasingly accounting for the cultural shifts of the past three decades. The declining membership of mainstream denominations, the rise of conservative (fundamentalists, evangelicals, charismatics, Pentecostals) and alternate religions (seekers, New Agers, Eastern religions), and the growing number of "new immigrants" all testify to a profoundly different religious landscape from that of fifty years ago. Because of these changes, historians like Thomas Tweed, Catherine Albanese, Joel Martin, and Peter Williams argue for a new type of narrative for American religious history. The introduction to Thomas Tweed's recently published Narrating U.S. Religious History (1997) provides an especially useful discussion on the changes the study of religious history is undergoing in the academy.

The most widely read and popular historical surveys in the past focused overwhelmingly on mainline Protestantism. Sydney Ahlstrom's A Religious History of the American People (1972), considered the masterpiece of religious history, certainly acknowledges religious diversity, but tells the story principally in terms of New England Puritans. Historians who still believe religious history must be taught with Protestants taking center stage agree with George Marsden's argument that the story of American religion, "if it is to hang together . . . must focus on . . . mainstream Protestants who were for a long time the insiders with disproportional influence in shaping American culture."

True, the Protestant establishment has influenced much of American culture and dominated religion in public life from the 1600s to the 1960s and beyond, but those who favor telling the stories of the marginalized and minority religious groups argue that the Protestant tale remains nevertheless only one story among many. It is an important story, but it has been told and retold at the expense of other stories. Other voices, motifs, and plots deserve a hearing, and all the more so since pluralism has been gradually replacing Protestant domination since the 1960s. Asian religions, new religious movements, popular religion, cultural religion, and woman's place in religion, all require attention after decades, even centuries, of focus solely on the white, male, European, Protestant (and primarily intellectual) religious tradition.

Historians agree that diversity characterizes a great deal of late-twentieth-century American religious life, but how much attention should be given and where to begin speaking of the diversity remain contested issues. Does one write and teach, as has traditionally been the case, about American religious history beginning primarily with the English Reformation and the Puritan migration to New England? (See Winthrop Hudson and John Corrigan's popular survey Religion in America [1992] or Edwin Gaustad's A Religious History of America [1990].) After all, much of America's formation as a nation is the story of Protestant pioneering and ascendancy. Or does one follow Catherine Albanese (America: Religions and Religion [1992] and Mary Farrell Bednarowski (American Religion: A Cultural Perspective [1984], who look at Catholics, Jews, Native Americans, and other religious groups before turning to the Protestant tradition? Albanese and Bednarowski believe they are making up for lost time on behalf of religious traditions heretofore disregarded and marginalized. As always, the teaching of history involves choices. These choices not only reflect personal values and priorities, but also the power historians have to grant pride of place to whomsoever they will in their rendition of religious life in America.

Links to online resources

Joanne C. Beckman is a Ph.D. candidate in American religious history at Duke University. She is currently working on her dissertation, Refashioning Eros: The Role of Romantic Love in Evangelical Courtship and Marriage Literature. Her areas of interest include the history of Christianity, ethnicity and religion, women and religion, American religious history of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, historiography, and evangelical scholarship. She has written articles on sabbatarianism, evangelicalism, Methodism, Billy Graham, and H. L. Mencken.

Address comments or questions to Professor Beckman through TeacherServe "Comments and Questions."

| Religious Liberalism and the Modern Crisis of Faith | The Rise of Fundamentalism | The Scopes Trial | Marcus Garvey | Roman Catholics and the American Mainstream | American Jewish Experience in the 20th Century | Islam in America | Religion in Post-World-War II America | The Christian Right | 20th-Century Links |

TeacherServe Home Page

National Humanities Center Home Page

Revised: October 2000

nationalhumanitiescenter.org