from the National Humanities Center |

|

| |

| NHC Home |

| The American Jewish Experience in the Twentieth Century: Antisemitism and Assimilation | ||

| Jonathan D. Sarna and Jonathan Golden Brandeis University ©National Humanities Center |

| |

The twentieth century witnessed the emergence of American Jewry on the world Jewish scene. As the century opened, the United States, with about one million Jews, was the third largest Jewish population center in the world, following Russia and Austria-Hungary. About half of the country's Jews lived in New York City alone, making it the world's most populous Jewish community by far, more than twice as large as its nearest rival, Warsaw, Poland. By contrast, just half a century earlier, the United States had been home to barely 50,000 Jews and New York's Jewish population had stood at about 16,000.

the Day of Atonement

near New York City, early 1900sImmigration provided the principal fuel behind this extraordinary American Jewish population boom. In 1900, more than 40 percent of America's Jews were newcomers, with ten years or less in the country, and the largest immigration wave still lay ahead. Between 1900 and 1924, another 1.75 million Jews would immigrate to America's shores, the bulk from Eastern Europe. Where before 1900, American Jews never amounted even to 1 percent of America's total population, by 1930 Jews formed about 3½ percent. There were more Jews in America by then than there were Episcopalians or Presbyterians.

This massive population transfer radically transformed the character of the American Jewish community.

It reshaped its composition and geographical distribution, resulting in a heavy concentration of Jews in East Coast cities, including some (like Boston) where Jews had never lived in great numbers before. It also realigned American Jewry's politics and priorities, injecting new elements of tradition, nationalism, and socialism into Jewish communal life, and seasoning its culture with liberal dashes of East European Jewish folkways. Although the American Jewish community retained significant elements from its German and Sephardic pasts (Sephardic Jews having originated in Spain and Portugal), the traditions of East European Jews and their descendants dominated the community. With their numbers and through their achievements, they raised its status both nationally and internationally.

Yiddish text: The Facts about the Candidate, by

Byron Andrews . . . Translated by Rabbi Simon . . .

Waltham, MA and New York, NYWorld War I confirmed American Jewry's new status in world Jewish affairs. America itself assumed greater international responsibilities at this time, and Jews followed suit.

Courtesy National Archives

(NWDNS-4-P-250)

Courtesy National Archives

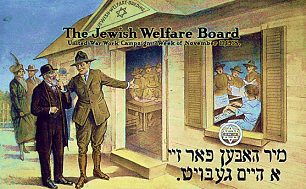

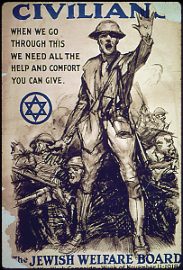

(NWDNS-4-P-47)Founded in 1917, the Jewish Welfare Board established centers for Jewish servicemen in the U.S. and overseas. It also led enlistment and fund-raising campaigns for the war effort.

As early as 1914, the American Jewish community mobilized its resources to assist the victims of the European war. Cooperating to a degree not previously seen, the various factions of the American Jewish community—native-born and immigrant, Reform, Orthodox, secular, and socialist—coalesced to form what eventually became known as the American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee. All told, American Jews raised 63 million dollars in relief funds during the war years and became more immersed in European Jewish affairs than ever before. They even joined in representing Jewish interests at the Paris Peace Conference after the war. Also, American Jews continued their intense involvement in Zionism—the movement to create a Jewish state in the Middle East (now Israel)—which further reflected their burgeoning sense of responsibility for the fate of Jews around the world.World War I ended the era of mass Jewish immigration to the United States, as wartime conditions and then restrictive quotas stemmed the human tide. Soon, for the first time in many decades, the majority of American Jews would be native born. Where the central focus of American Jewish life had been concentrated on problems of immigration and absorption, American Jewry now entered a period of stable consolidation.

The children of immigrants moved up into the middle class and out to more fashionable neighborhoods, creating new institutions— synagogue-centers, progressive Hebrew schools, and the like—as they went. History had proved that East European Jews would Americanize with a vengeance. The question now was whether, as Americans, they would still remain Jews. Programs designed to ensure that they would became high community priorities.

Courtesy Florida State ArchivesWith stability and the rise of a new generation came a growing commitment to communal unity. Descendants of earlier Central European Jews and the more recent East European Jews had been drawing closer together in America even before World War I. After the war, with the growth of antisemitism at home and abroad as well as the economic and social challenges posed by the Great Depression of the 1930s, this process accelerated. Antisemitism peaked in America in the interwar years, and was practiced in different ways by even highly respected individuals and institutions. Private schools, camps, colleges, resorts, and places of employment all imposed restrictions and quotas against Jews, often quite blatantly. Leading Americans, including Henry Ford and the widely listened-to radio priest, Father Charles Coughlin, engaged in public attacks upon Jews, impugning their character and patriotism. In several major cities, Jews also faced physical danger; attacks on young Jews were commonplace. When coupled with the economic hardship

wrought by the Great Depression, it is no surprise that Jews during these years sought to bury their differences and stress their interdependence. Leaving old world divisions behind, they began to coalesce into an avowedly American Jewish community—a community that could attempt, at least on some issues, to unite in self-defense.

of Miami's oldest synagogue, 1931

Courtesy Florida State ArchivesEven as the community was uniting, however, it was being rent asunder in new ways. The three-part religious division among Orthodox, Conservative, and Reform Jews, firmly institutionalized in this period, gave expression to longstanding intracommunal conflicts over rituals, beliefs, and attitudes toward tradition and change. Zionism and Communism proved even more divisive since they raised fundamental questions concerning the meaning of American Jewish life and the obligations of Jews to the country in which they lived.

| Religious Liberalism and the Modern Crisis of Faith | The Rise of Fundamentalism | The Scopes Trial | Marcus Garvey | Roman Catholics and the American Mainstream | American Jewish Experience in the 20th Century | Islam in America | Religion in Post-World-War II America | The Christian Right | 20th-Century Links |

TeacherServe Home Page

National Humanities Center Home Page

Revised: October 2000

nationalhumanitiescenter.org