from the National Humanities Center |

|

| |

| NHC Home |

|

Islam in America: From African Slaves to Malcolm X | ||

| Thomas A. Tweed University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill ©National Humanities Center |

| |

When students think of Islam—if they do at all—they might summon an image of Denzel Washington playing a stern and passionate Malcolm X in Spike Lee's 1992 film, or maybe they imagine Louis Farrakhan on the speaker's platform at the Million Man March in 1995. Some might have encountered Middle Eastern Muslims on the nightly news, mostly as "fundamentalists" and "terrorists." A few have met immigrant Muslims in their neighborhood. Muslim students might be among their classmates. But Muslims are more diverse than popular images allow, and American Muslim history is longer than most might think, extending back to the day that the first slave ship landed on Virginia's coast in 1619. It encorporates two groups—Muslims from other countries who migrated to America by force or by choice, and African Americans who created Muslim sects in the twentieth century. Thus, a consideration of the Islamic presence in America provides a new perspective on several important (and familiar) issues that will be used to organize this essay:

- What is the history of slavery in the United States?

- How have immigrants resisted and accommodated American culture?

- What were African Americans' experiences in the northern cities after the Great Migration?

- How has African-American Islam addressed race relations since the 1960s?

- Is America a Christian nation?

At first, you will need to introduce Islam to your students, and a helpful way to do this is to invite their responses to the word "Muslim." What comes to mind when they hear the word? Write their responses on the board without comment, and then use the list to establish the dominant images of Muslims—for example, as militants, extremists, newcomers. Then you can begin to contest these impressions and establish that Islam is a diverse and long-standing American religion—one that has had a significant presence in the United States.

At this point you will need to introduce the basic beliefs and practices of the world's one billion Muslims, most of whom live in Asia, not in the Middle East as most Americans presume. As in Christianity and Judaism, Islam (which is second only to Christianity in worldwide adherents) includes a number of communities or branches. The two major groups are Sunni Muslims, who constitute about 85 percent of Muslims, and Shii (or Shiite) Muslims, who account for 15 percent of the world's Islamic population. All traditional groups are represented among the five million Muslims in the United States, along with some new movements that have been cultivated on American soil.

Despite their diversity, Muslims have a good deal in common. They look to the Qu'ran— the sacred book that records the message of Allah [God] as it was revealed to his final prophet, Muhammed (A.D. ca. 570-632), and they seek to follow the example (sunna) of the prophet. All accept the Five Pillars of Islam, the basic beliefs and duties of Muslims:

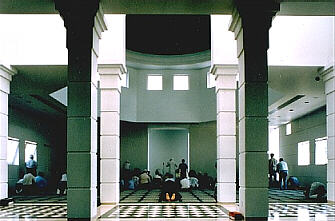

Muslims in prayer, Long Island, New York

Courtesy Islamic Center of Long Island

- A profession of faith (shahada). All Muslims must proclaim "There is no God but Allah and Muhammed is his prophet." Note here that Muhammed is not God in Muslim theology but rather a spokesperson or mouthpiece for the divine.

- Prayer (salat). All Muslims pray five times daily while facing the holy city of Mecca in Saudi Arabia.

- Alms (zakat). Faith also means outreach. To give thanks and follow the example of Muhammed, Muslims with the economic means must give alms to those who are less fortunate.

- Fasting (sawm or siyam). Muslims who are physically able are to fast from dawn to dusk during the ninth month (Ramadan) of the Islamic calendar.

- A pilgrimage (hajj) to Mecca. At least once in their lives, all Muslims who are able must make a pilgrimage to the Great Mosque in the holy city of Mecca, toward which they have knelt while praying five times daily during their lives. (Chapter seventeen of The Autobiography of Malcolm X offers a vivid account of this pilgrimage, which was life-transforming for him. It was on hajj, he recounts, that he first glimpsed the possibility that people of different races could get along.)

Slavery and Islam

A small but significant proportion of African slaves, some estimate 10 percent, were Muslim. You might tell the story of Omar Ibn Said (also "Sayyid," ca. 1770-1864), who was born in Western Africa in the Muslim state of Futa Toro (on the south bank of the Senegal River in present-day Senegal). He was a Muslim scholar and trader who, for reasons historians have not uncovered, found himself captive and enslaved. After a six-week voyage, Omar arrived in Charleston, South Carolina, in about 1807. About four years later, he was sold to James Owen of North Carolina's Cape Fear region. In 1819 a white Protestant North Carolinian wrote to Francis Scott Key, the composer of The Star Spangled Banner, to request an Arabic translation of the Bible for Omar, and apparently Key sent one. Historians dispute how much the African Muslim leaned toward Christianity in his final years, but Omar's notations on the Arabic bible, which offer praise to Allah, suggest that he retained much of his Muslim identity, as did some other first-generation slaves whose names have been lost to us. (Omar's Arabic bible, which has recently been restored, is housed in the library of Davidson College in North Carolina.)

Muslims and Immigration, 1878-1924

Most history courses cover the immigrants who changed America's population throughout the nineteenth century. You might point out these immigrants were not all European or Christian. Many were Chinese and Japanese migrants who practiced Buddhism and other Asian traditions. Thousands of Muslims came as well, and most of these first Islamic immigrants were Arabs from what was then Greater Syria. These Syrian, Jordanian, and Lebanese migrants were poorly educated laborers who came seeking greater economic stability. Many returned, disenchanted, to their homeland. Those who stayed suffered isolation, although some managed to establish Islamic communities, often in unlikely places. By 1920, Arab immigrants worshiped in a rented hall in Cedar Rapids, Iowa, and they built a mosque of their own fifteen years later. Lebanese-Syrian communities did the same in Ross, North Dakota, and later in Detroit, Pittsburgh, and Michigan City, Indiana. Islam had come to America's heartland.

The first wave of Muslim immigration ended in 1924, when the Asian Exclusion Act and the Johnson-Reed Immigration Act allowed only a trickle of "Asians," as Arabs were designated, to enter the nation.

African-American Islam in the Urban North

A Euro-American, Mohammed Alexander Webb (1847-1916), proclaimed himself a Muslim at the World's Columbian Exposition in Chicago in 1893, but converts have been more prominent among Americans of African descent, especially those who followed the mass migrations of southern blacks to northern cities beginning in the early decades of the twentieth century. Noble Drew Ali established a Black nationalist Islamic community, the Moorish Science Temple, in Newark, New Jersey in 1913. After his death in 1929, one of the movement's factions found itself drawn to the mysterious Wallace D. Fard, who appeared in Detroit in 1930 preaching black nationalism and Islamic faith. Fard founded the Nation of Islam there in the same year. After Fard's unexplained disappearance in 1934, Elijah Muhammed (1897-1975) took over, and he attracted disenchanted and poor African Americans from the urban north. They converted for a variety of reasons, but, for some, the poverty and racism in those cities made the Nation of Islam's message about "white devils" (and "black superiority") plausible.

Race Relations since the 1960s

Elijah Muhammed won an important convert when Malcolm Little (1925-1965) joined the faith in a prison cell. Malcolm X, the name he took to signal his lost African heritage, became a public figure during the 1960s, although he separated himself from the Nation of Islam before his death. After Elijah Muhammed's death in 1975, the movement split. One branch, under the leadership of the fifth son of Elijah Muhammed, moved closer to the beliefs and practices of Islam as it is practiced in most of the world. This group, which would later change its name to the American Muslim Mission, is the largest African-American Islamic movement. The much smaller Nation of Islam, which the American Muslim Mission and other Islamic groups condemn as racist and unorthodox, is much more familiar to most Americans. Many American Muslims would claim that the Nation of Islam, led by Louis Farrakhan, is not representative of either immigrant or convert Islam in the United States.

As you teach the Nation of Islam, you might ask students what the history of African-American Islam since the Great Migration tells us about race relations. Why were Malcolm X and others in northern cities so willing to believe that European Americans were "white devils"? In what sense, you might ask, is the Nation of Islam's sacred story about the origin of whites as the mistake of a black scientist a "truthful" representation of many African Americans' experience?

Muslims and the New Immigrants after 1965

If you are able to reach the post-1965 period in your class, you might reintroduce Muslims in a discussion of demographic changes in contemporary America. Palestinian refugees arrived after the creation of Israel in 1948. More important for the history of American Islam, the McCarran-Walter Act of 1952 relaxed the quota system established in 1924, thereby allowing greater Muslim immigration. The gates opened even more widely after the 1965 revisions of the immigration law. Since then, Muslim migrants have fled oppressive regimes in Egypt, Iraq, and Syria; and South Asian Muslims, as from Pakistan, have sought economic opportunity. By the 1990s, Muslims had established more than six hundred mosques and centers across the United States.

Islamic Cultural Center of New York

Islamic Center of West Virginia Islamic Center of Long Island Courtesy Muslimsonline.com, the Islamic Cultural Center of New York,

and the Islamic Assn. of West Virginia

Is America a Christian Nation?

Toward the end of your discussion of Islam in America, you might raise this final issue concerning religion and national identity. Islam may soon be the second largest American faith after Christianity, if it is not already. Estimates vary widely, and a moderate estimate is five million American Muslims in 1997—more than Episcopalians, Quakers, and Disciples of Christ. When recounting this to students, and recalling the history of Islamic slaves and the early debates about the First Amendment, you might ask students whether America is a Christian nation as some have proclaimed. Could we, you might ask to focus the discussion, elect a Muslim president? If so, would she (while we are imagining, let's get bold!) view this land as a New Israel or take her presidential oath on a Christian Bible, as has been traditional?

Links to online resources

Related info in "Getting Back to You"

Thomas A. Tweed holds a Ph.D. from Stanford University in Religious Studies and is currently the Zachary Smith Professor of Religious Studies at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Dr. Tweed is the author of Our Lady of the Exile: Diasporic Religion at a Cuban Catholic Shrine in Miami (Oxford University Press, 1997) and the editor of Retelling U.S. Religious History (California University Press, 1997). He most recently co-edited, with Stephen Prothero, Asian Religions in America: A Documentary History (Oxford University Press, 1999).

Address comments or questions to Professor Tweed through TeacherServe "Comments and Questions."

TeacherServe Home Page

National Humanities Center Home Page

Revised: December 2004

nationalhumanitiescenter.org