Rooted in Africa, Raised in America:

The Traditional Arts and Crafts of

African-Americans Across Five Centuries

Rarely do studies of slavery mention the valuable skills and tangible creations of the millions of Africans brought to the New World. Much is made—and rightly so—of African talents in storytelling, music, and dance but these modes of creative performance do not adequately describe the full range of Africa’s contributions to American culture. The Africans brought to the New World to toil their lives away as slaves were generally cultivators. They also possessed a wide range of skills that they had used for generations to wrest a living from the land and among these millions of unwilling immigrants were many skilled artisans. They included builders who erected houses for their families and other structures that sheltered their annual harvests. When confronting the challenges of living in the dense tropical forests of their homelands, they turned to their local blacksmiths who forged the necessary iron tools that allowed them to clear and maintain their garden plots. Basket makers provided them with various containers that allowed crops to be harvested and stored until needed. Potters turned local clays, found most often along the banks of numerous rivers and streams, into useful cooking and storage vessels. Other domestic implements, items like serving bowls and drinking cups, could be fashioned from gourds of varying sizes and baskets were made from reeds, palm leaves, and a wide variety other vegetal materials. Over the course of several millennia African populations developed the means to live successfully within a challenging environment of extreme heat, prolonged rain, and dense forest cover. Labeled by Europeans as savages, these people possessed a wide array of tangible skills that would ultimately prove to be precious immigrant gifts that they would contribute to the making of the Americas. Unfortunately for them, they were within easy reach of slave traders whose ships made regular calls along almost five thousand miles of Africa’s coastal shores.

Asante-style drum.The well-documented horrors of captivity in the foul holds of slave ships drive from our minds any images except those of horrible misery and suffering. Yet objects of considerable creativity, on occasion, also made the same voyage from Africa to the Americas. There is today in the British Museum a drum carved from a section of a tree trunk that was collected in Virginia some time between 1730 and 1745. The drum’s shape, materials, and mode of decoration are so distinctive that the instrument can confidently identified as one made by a person belonging to the Akan-speaking peoples who still reside in the modern nation of Ghana. There can be little doubt that this musical instrument was used in some plantation context almost half a century before the American Revolution. The presence of such an unquestionably African object in the Americas indicates that the captives who were taken far from their homeland were still able to retain selected aspects of their native identities. It was more often the case that elements of their culture—language, religion, and foodways to name a few—would over time become blended or creolized expressions as Africans evolved into African-Americans.

Banjo being played at slave

quarter with a drum

accompaniment. 18th Century.In plantation societies the playing of drums was generally outlawed due to the fear by slave owners that such instruments could be used to send messages related to rebellion and escape. Such prohibitions did not however apply to other African musical instruments such as the banjo. In fact, the appealing sound of the banjo would, by the dawning of the nineteenth century, ignite a national fascination for its compelling combination of melody and percussion. As a player’s fingers plucked a lively tune on the strings, he would simultaneously mark the song’s beat when his hand tapped the skin stretched over the sounding chamber. Functionally the banjo joined the lute to the drum, an act that fused melody with a strong rhythmic punctuation. This combination of tune and percussion in a single instrument proved to be so appealing that banjo tunes that were first heard in plantation contexts are played today. However, the banjo is now so thoroughly associated with the Appalachian highlands and Anglo-American musicians that only a handful of enthusiasts are aware of either the banjo’s African origins or its long history among African-American players.

African Potter and Colonoware samples.

©2005 African Diaspora Archaeology Network.Archaeologists, who have probed the grounds on old plantation sites dating back to the seventeenth century, regularly turn up fragments of unglazed earthenware pottery. Seeming to be very crude when compared to the stoneware vessels commonly in use in Euro-American households, these items were initially presumed to have been made by Native Americans of the colonial period who perished shortly after the arrival of the first European settlers. Initially labeled as Colono-ware, it is now clear that many of these pieces were fashioned by Africans. Consequently these rough earthenware vessels should be recognized as Afro-Colono pieces if not, in some cases, simply as examples of African pottery. During the colonial era South Carolina’s enslaved blacks outnumbered white people by a ratio of four to one and, given this numerical dominance, planters found that they could only effectively supervise their slaves when they were out in the fields. Consequently, the routines carried out in their domestic quarters could—and did—reconnect them to some of the practices of their African homelands as they fashioned their own clay vessels and used them to cook their meals according their own preferences. The African quality of their domestic routines was so evident to one eighteenth-century visitor that he would write that “Carolina looks more like a negro country than like a country settled by white people.” At plantation sites across the Carolina lowcountry archaeologists have discovered that over ninety percent of the ceramic evidence consists of fragments of Colono-ware, a finding that suggests that slaves controlled far more of their domestic routine than was previously suspected.

Given that Africans were the largest population group in South Carolina during the colonial era, it should not be too surprising that black Carolinians would continue to use their African languages when conversing among themselves. But even when they had developed a creolized variant called Gullah, this new language still retained many African elements. They also developed an Africanized spatial “language” that was used in the design and layout of their quarters. To some white observers these buildings were too small and thus seemed uncomfortably crowded. This is because when English rules of measure were employed, room sizes were generally in range of 264 square feet (16 feet x 16 feet). In West African buildings rooms are considerably smaller being, on average, closer to 100 square feet (10 feet x 10 feet). The Afro-Carolinian average room size, based on a sample of excavated foundations, was 120 square feet (approximately 11 feet x 11 feet). These proportions suggest that slaves continued to employ a sense of proportion that recalled the traditional house types found all along the Guinea Coast region from Sierra Leone to Cameroon.Filming “Digging for Slaves.”Wall trench and post holes

in slave quarter.

Whenever African-Americans were able to exert a degree of control over their working or living conditions, there usually emerged interesting tangible signs of their concerns 1859 Jar

by David Drake

(a.k.a. Dave the Potter).

25-Gallon Jar

by David Drake

(a.k.a. Dave the Potter).and values. As early as the 1820s in Edgefield District of western South Carolina, for example, slave labor was used extensively in the manufacture of stoneware pottery. The most noteworthy black potter in the area was David Drake, an extraordinarily skilled man who is credited with producing the largest vessels ever made during the antebellum period—huge crocks with holding capacities of almost fifty gallons.

Beyond the achievement of creating vessels that were so monumental in scale, Drake also added inscriptions in the form of witty rhymed couplets like “A large jar which has four handles/ pack it full of fresh meat—then light candles” or “Good for lard/ or holding fresh meat/ Blest we were when/ Peter saw the folded/ sheet.” But he could also offer more sobering statements on his captivity: “Dave belongs to Mr. Miles/ wher[e] the oven bakes & the pot biles.” That he would display his literacy in public was a dangerous gesture since South Carolina law required that any slave who was literate was to be sold out of the state because of his ability to send secret messages to other slaves who might be plotting escapes or even rebellions. But because Drake was so skilled and could clearly make the sorts of large storage jars required by the bigger plantations, the criminal penalties for his literacy were apparently overlooked. That Drake’s craft skills had evidently earned him a rare dispensation from the penalties of the local slave codes would signal to other slaves that skill was a potential pathway to privilege. Face jugs attributed to a slave potter in

Edgefield, South Carolina, about 1850.While the potteries of the Edgefield District were established to satisfy planters needs for utilitarian wares, by the middle decades of the nineteenth century some African-American potters were making small vessels that were sculpted into the form of human heads. Generally about five inches tall (although one example measures less than an inch-and-a-half), their purpose has never been discovered and thus remains open to speculation. It is, however, worth noting that these small face pots strongly resemble wooden sculptures known in the Congo region of central Africa which also have shiny white material inserted in them to mark eyes and teeth in exactly the same manner as the Edgefield vessels. The opportunity to develop pottery skills allowed African-Americans to develop new skills even as they as retained some aspects of an ancestral tradition.

Sherry Byrd and her “Home-grown/

Hand-made/Passed-on-Family” quilt.

While quilted bedcovers were not used in the tropical homelands of enslaved Africans, they soon learned how to make them. Requiring thousands of tiny stitches to attach the colorful quilt top to a plain back, assembling a quilt could take months to complete. Fannie Moore, who was still a child when slavery was abolished, recalled how her mother quilted in her cabin making bedcovers for “the white folks” as well as for her own family. One particularly noteworthy quilt decorated with images of chalices was made in 1860 by some of the enslaved women of Mimosa Hall plantation in East Texas. Created on the occasion of a visit by an Anglican bishop, the quilt is today a high prized work of art owned by the American Museum in Britain located at Claverton Manor in Bath, England. Bedcovers of this sort rigorously follow a strict grid pattern typical of most Anglo-American quits and in this instance black quilters contributed only their labor as the quilt was assembled. But over their years of captivity, black quilters evolved their own approach to quilt-making by developing a style open to imaginative patterns that break away from the usual Euro-American patterns based on a strict repetitive geometry. Contemporary African-American quilter Sherry Bryd actually rejects old patterns saying “I don’t like to do the same things over and over again, and so I just kind of build my own quilts as I sit at the machine.”

The improvisatory mode that she describes has led many quilters to experiment with novel notions of quilt design. The most adventuresome proceed intuitively working out ideas that they have never tried before although they still seem to be, in some way, familiar. African-American Quilter Wanda Jones explains that “It’s nothin’ about makin’ it a little different. It’s still the same pattern. You just add somethin’ of your own to it.” A fusion of past and present occurs while a quilter is sorting out some of the various ways that she might assemble her quilt. This review process has led ultimately to a preference for a set of constantly evolving patterns. The fluid design process seen in so many contemporary African-American quilts is analogous to the open-ended approach to musical composition that can be heard in blues and jazz performances where improvisational technique constantly interrupts regularized notions of tone and time.

Bars and Blocks,

Mary Lee Bendolph,

2003.

Bricklayer,

Mary Lee Bendolph

and Ruth P. Mosely.

Recently there has been much public acclaim for the quilts produced in the small central Alabama town of Gee’s Bend. These exciting bedcovers have been displayed, so far, at twelve major museums all across the country and can be seen on a host of websites. Marked by bold color choices and patterns that break away from the expected regularized patterns of repeated blocks, these quilts strike most viewers as works of are equivalent to abstract paintings.

Actually the Gee’s Bend quilts derive from so-called “throw together” quilts known to southern blacks as far back as the sharecropper era and, in some cases, even to slavery times. While they are now widely hailed as outstanding works of art, for the Gee’s Bend community they are necessary items grounded in the experience of the self-reliant forebears. Some quilters see in the quilting process an expression of homage to ancestors who survived conditions much worse than what they may have to confront today. Contemporary Gee’s Bend quilter Mary Lee Bendolph acknowledges a feeling for the past in her work when she selects the materials for her quilts: “Old clothes carry something with them. You can feel the presence of the person that used to wear them. It has spirit in them. Even if I don’t even know the person, I know someone wore those pants, and it feels lovely and warm to me.” But the past is only one of the influences that she brings together with her own personal insights and preferences as she creates a quilt: “I never try to quilt altogether like anybody … It’s better if you do what you are supposed to do than to try and copy somebody else.” In the hands of an artist like Bendolph an old art form like quilting remains fresh and relevant.

Contemporary African-American folk artists find themselves faced with the possibility of honoring the legacy of the past even as they look for a way to make their own mark. Philip Simmons, a renowned blacksmith who worked in Charleston, South Carolina for seventy years, was trained by Peter Simmons (no relation), a man who was born a slave. Peter Simmons’ history in ironwork traces back at least as far as the first decades of the nineteenth century. But when asked about the importance of this history in carrying on his ancient trade, Philip Simmons suggests that the future always held more of an attraction for him because of the appeal of the unknown: “After all those many years [of working], I’m still learning things. I’m still doing things I have never done before. There is always something you can learn. Blacksmithing, there’s always something new to learn.”

So often the dominant interest in history is focused on looking back over time in order to answer questions related to origins. While the study of the historical record is important, Simmons encourages us to alter our perspective and to consider how the great arc of history also reaches forward to contemporary generations. He suggests that if we have a good understanding of older precedents and the desire look at them with care, we might be able to see how historical influences can move beneficially on into the future. Simmons’s suggestion about the utility of traditional knowledge in the present can be seen daily in the streets of Charleston, South Carolina. Philip Simmons, 1982. Photographed by Tom Pich,

for the National Endowment for the Arts,

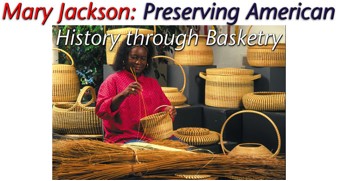

National Heritage Fellows. Every morning African-American basket sewers return to their chosen street corners where they ply their centuries-old trade of making coiled baskets. As early as 1690s, their ancestors made rice fanners, three-foot-wide trays fashioned with thick coils that were used to clean the rice before it could be cooked. They also made a wide assortment of containers that were used both in their homes and in the fields. The baskets made for home use tended to be smaller and thus their coils were thinner and their shapes more elegant than the baskets used for field tasks. When a series of hurricanes at the end of the nineteenth century destroyed the vast rice fields that stretched from North Carolina to Florida, there was no longer a need for most work baskets but the more resourceful basket makers began to focus on flower baskets and other decorative forms that might be sold to tourists. Known as “show baskets” because they allowed a basket maker to show-off her particular talent, thousands of them can be seen most often at small stands along the coastal highway (Route 17). Consequently, the public presence of basket sewers has become an exotic feature of the local scene that can lure tourists to Carolina lowcountry.

During the last quarter of the twentieth century, sweetgrass basket sewers (and there are hundreds of them) were celebrated in several museum exhibitions, both locally and nationally, and as a result of this attention their baskets have come to be celebrated as the product of an unbroken tradition that has endured into its fourth century.  One of the great contemporary stars, among many highly talented basket sewers, is Mary Foreman Jackson who has placed her works at an impressive list of notable museums that include: the Smithsonian American Art Museum, the Boston Museum of Fine Arts, and the Philadelphia Museum of Art. Jackson’s baskets are so highly regarded that when prominent figures visit South Carolina they presented with one of her baskets as a remembrance of the event. Included among these dignitaries are: Pope John Paul II; Charles, Prince of Wales, and the Emperor and Empress of Japan. That a humble tool for cleaning rice could give rise to a prestigious art form used to honor the world’s most noteworthy figures, speaks volumes about the creative energies embedded in the African-American community and the enduring power of their traditions. Clearly a community that can produce such talented artists deserves closer study so that their hidden virtues might, one day, become a source of national pride.

One of the great contemporary stars, among many highly talented basket sewers, is Mary Foreman Jackson who has placed her works at an impressive list of notable museums that include: the Smithsonian American Art Museum, the Boston Museum of Fine Arts, and the Philadelphia Museum of Art. Jackson’s baskets are so highly regarded that when prominent figures visit South Carolina they presented with one of her baskets as a remembrance of the event. Included among these dignitaries are: Pope John Paul II; Charles, Prince of Wales, and the Emperor and Empress of Japan. That a humble tool for cleaning rice could give rise to a prestigious art form used to honor the world’s most noteworthy figures, speaks volumes about the creative energies embedded in the African-American community and the enduring power of their traditions. Clearly a community that can produce such talented artists deserves closer study so that their hidden virtues might, one day, become a source of national pride.

Guiding Student Discussion

Deriving history from artifacts is a tricky proposition for most scholars because they are so used to gathering information by reading written documents. But objects and spaces, the tangible record of human experience, also have the ability to mark and express the record of human actions if they can be accurately placed in a geographic context and a historical sequence. Once archaeologists can link a dusty sherd of pottery to a person from a specific location during particular period, they can use that fragment to carry our minds back to that very same moment. By attending carefully to the materials, size, construction, decoration, and use of an object, whether it is as small as a pin or a large as house, a detailed biography can be constructed of any artifact (see Fleming’s cited below for a model). With that profile in hand, one can turn then to a particular type of artifact—a quilt, for example—and compare it to others of the same class and then make useful observations of similarities and differences over time or across regions. What emerges from such an inquiry is something of the life history of the object that might indicate the virtues or flaws of a particular quilt pattern. If enough quilts are sampled as group, it may be possible to learn something about the artistic direction followed by a particular community. My book The Afro-American Tradition in Decorative Arts samples a wide array of topics that might be considered for class or individual projects: basketry, woodcarving, weaving, quilting, pottery, boatbuilding, blacksmithing, carpentry.

Since we live an era where most people are consumers rather than producers of the things they use every day, life in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries is bound to appear very alien, if not irrelevant. Students might be benefit from assignments that require them to inspect aspects of the daily routines of slaves. Reading selected slave narratives, particularly those collected by interviewers working for the Federal Writer’s Program, will take students directly into the slave quarters and their work areas (see Yetman). Often filled with memories of harsh treatment and cruel exploitation, their accounts also describe instances of diligent work and craft skills. The evident pride that some people express indicates that their statements made by material means served as a partial therapy for their cruel treatment. By creating a wide array of domestic items that they could use in their quarters, enslaved African-Americans proved that they were more the mere property. Gabe Lance, who worked for many years in the rice fields of South Carolina, when asked about life during the years before the Civil War, responded with apparent pride and a measure of bravado “Missus, Slavery time people done something!” It would be very therapeutic if students could understand that enslaved people were more than the sum of their brutalization—and further that a legacy, rooted in African aesthetic that continues to live on, can still be witnessed via a considerable number of tangible signs.

NHC Home | TeacherServe | Divining America | Nature Transformed | Freedom’s Story

About Us | Site Guide | Contact | Search